Aromatic Allotropes of Carbon

– In this subject, we will talk about Aromatic Allotropes of Carbon.

Aromatic Allotropes of Carbon

What do you get when you make an extremely large polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbon, with millions or billions of benzene rings joined together? You get graphite, one of the oldest-known forms of pure elemental carbon.

– Let’s consider how aromaticity plays a role in the stability of both the old and the new forms of carbon.

Allotropes of Carbon: Diamond

– We don’t normally think of elemental carbon as an organic compound.

– Historically, carbon was known to exist as three allotropes (elemental forms with different properties): amorphous carbon, diamond, and graphite.

– “Amorphous carbon” refers to charcoal, soot, coal, and carbon black. These materials are mostly microcrystalline forms of graphite.

– They are characterized by small particle sizes and large surface areas with partially saturated valences.

– These small particles readily absorb gases and solutes from solution, and they form strong, stable dispersions in polymers, such as the dispersion of carbon black in tires.

– Diamond is the hardest naturally occurring substance known.

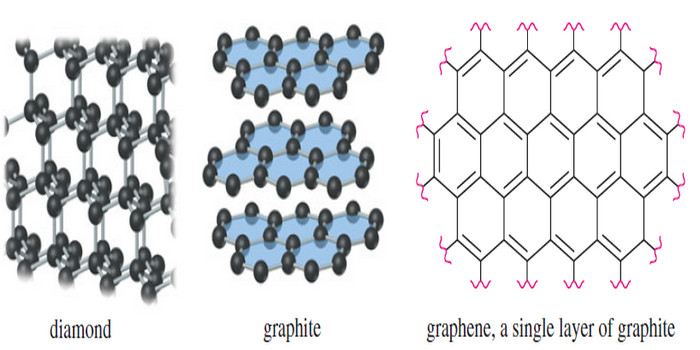

– Diamond has a crystalline structure containing tetrahedral carbon atoms linked together in a three-dimensional lattice (Figure).

– This lattice extends throughout each crystal, so that a diamond is actually one giant molecule.

– Diamond is an electrical insulator because the electrons are all tightly bound in sigma bonds (length 1.54 Å, typical of C-C single bonds), and they are unavailable to carry a current.

Graphite

– Graphite has the layered planar structure shown in Figure above. Within a layer, the C-C bond lengths are all 1.415 Å which is fairly close to the C-C bond length in benzene (1.397 Å).

– Between layers, the distance is 3.35 Å which is about twice the van der Waals radius for carbon, suggesting there is little or no bonding between layers.

– The layers can easily cleave and slide across each other, making graphite a good lubricant.

– This layered structure also helps to explain graphite’s unusual electrical properties: It is a good electrical conductor parallel to the layers, but it resists electrical currents perpendicular to the layers.

– We picture each layer of graphite as a nearly infinite lattice of fused aromatic rings.

– All the valences are satisfied (except at the edges), and no bonds are needed between layers.

– Only van der Waals forces hold the layers together, consistent with their ability to slide easily over one another.

– The pi electrons within a layer can conduct electrical currents parallel to the layer, but electrons cannot easily jump between layers, so graphite is resistive perpendicular to the layers.

– Because of its aromaticity, graphite is slightly more stable than diamond, and the transition from diamond to graphite is slightly exothermic (ΔH° = -2.9 kJ/mol or -0.7 kcal/mol).

– Fortunately for those who have invested in diamonds, the favorable conversion of diamond to graphite is exceedingly slow.

– Diamond (3.51 g/cm3) has a higher density than graphite (2.25 g/cm3) implying that graphite might be converted to diamond under very high pressures.

– Indeed, small industrial diamonds can be synthesized by subjecting graphite to pressures over 125,000 atm and temperatures around 3000 °C, using catalysts such as Cr and Fe.

– Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov (University of Manchester) received the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics for producing and characterizing graphene, which is a single layer of graphite one atom thick.

– They used adhesive tape to pull one layer away from the surface of a piece of graphite. Single-layer graphene is transparent, strong, and an excellent electrical conductor. It has been used to make transistors, and it holds great promise for touch-screen monitors if it can ever be mass-produced in large sheets.

Fullerenes

– Around 1985, Kroto, Smalley, and Curl (Rice University) isolated a molecule of formula C60 from the soot produced by using a laser (or an electric arc) to vaporize graphite.

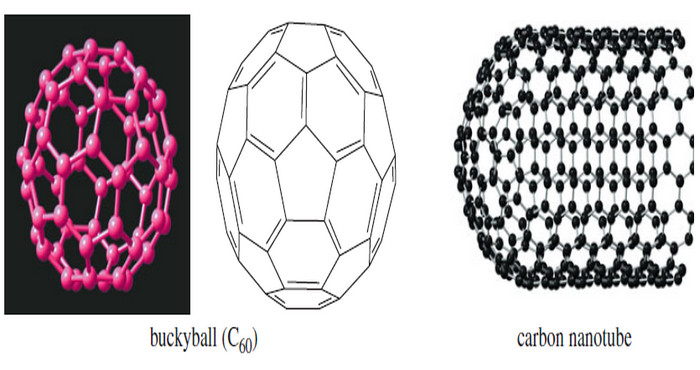

– Molecular spectra showed that C60 is unusually symmetrical: It has only one type of carbon atom by 13C NMR (δ 143 ppm) , and there are only two types of bonds (1.39 Å and 1.45 Å).

– The Following Figure shows the structure of C60 which was named buckminsterfullerene in honor of the American architect R. Buckminster Fuller, whose geodesic domes used similar five- and six membered rings to form a curved roof.

– The C60 molecules are sometimes called “buckyballs,” and these types of compounds ( C60 and similar carbon clusters) are called fullerenes.

– A soccer ball has the same structure as C60 with each vertex representing a carbon atom. All the carbon atoms are chemically the same.

– Each carbon serves as a bridgehead for two six-membered rings and one five-membered ring.

– There are only two types of bonds: the bonds that are shared by a five-membered ring and a six-membered ring (1.45 Å) and the bonds shared between two six-membered rings (1.39 Å).

– Compare these bond lengths with a typical double bond (1.33 Å), a typical aromatic bond (1.40 Å), and a typical single bond (1.48 Å between sp2 carbons).

– It appears that the six-membered rings are aromatic, but the double bonds are partially localized between the six-membered rings, (Figure above).

– These double bonds are less reactive than typical alkene double bonds, yet they do undergo some of the addition reactions of alkenes.

– Nanotubes (Figure) were discovered around 1991. These structures begin with half of the C60 sphere, fused to a cylinder composed entirely of fused six-membered rings (as in a layer of graphite).

– Nanotubes have aroused interest because they are electrically conductive only along the length of the tube and they have an enormous strengthto- weight ratio.

References:

- Organic chemistry / L.G. Wade, Jr / 8th ed, 2013 / Pearson Education, Inc. USA.

- Fundamental of Organic Chemistry / John McMurry, Cornell University/ 8th ed, 2016 / Cengage Learningm, Inc. USA.

- Organic Chemistry / T.W. Graham Solomons, Craig B. Fryhle , Scott A. Snyder / 11 ed, 2014/ John Wiley & Sons, Inc. USA.

- Unergraduate Organic Chemistry /Dr. Jagdamba Singh, Dr. L.D.S Yadav / 1st ed, 2010/ Pragati prakashan Educational Publishers, India.