Spin-Spin Splitting in ¹H NMR Spectra

– In this topic, we will discuss The Spin-Spin Splitting in ¹H NMR Spectra.

Theory of Spin-Spin Splitting

– A proton in the NMR spectrometer is subjected to both the external magnetic field and the induced field of the shielding electrons.

– If there are other protons nearby, their small magnetic fields also affect the absorption frequencies of the protons we are observing.

– Consider the spectrum of 1,1,2-tribromoethane (Figure 1).

– As expected, there are two signals with areas in the ratio of 1 : 2.

– The smaller signal (Ha) appears at δ 5.7, deshielded by the two adjacent bromine atoms.

– The larger signal (Hb) appears at δ 4.1.

– These signals do not appear as single peaks but as a triplet (three peaks) and a doublet (two peaks), respectively.

– This splitting of signals into multiplets, called spin-spin splitting, results when two different types of protons are close enough that their magnetic fields influence each other. Such protons are said to be magnetically coupled.

– Spin-spin splitting can be explained by considering the individual spins of the magnetically coupled protons.

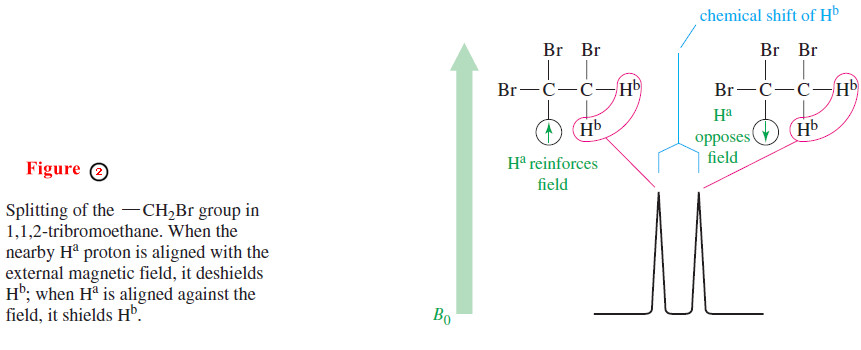

– Assume that our spectrometer is scanning the signal for the Hb protons of 1,1,2-tribromoethane at δ 4.1 (Figure 2).

– These protons are under the influence of the small magnetic field of the adjacent proton,Ha.

– The orientation of is not the same for every molecule in the sample.

– In some molecules, Ha is aligned with the external magnetic field, and in others, it is aligned against the field.

– When Ha is aligned with the field, the Hb protons feel a slightly stronger total field: They are effectively deshielded, and they absorb at a lower field.

– When the magnetic moment of the Ha proton is aligned against the external field, the Hb protons are shielded, and they absorb at a higher field.

– These are the two absorptions of the doublet seen for the Hb protons.

– About half of the molecules have Ha aligned with the field and about half against the field, so the two absorptions of the doublet are nearly equal in area.

Spin-spin splitting is a reciprocal property. If one proton splits another, the second proton must split the first.

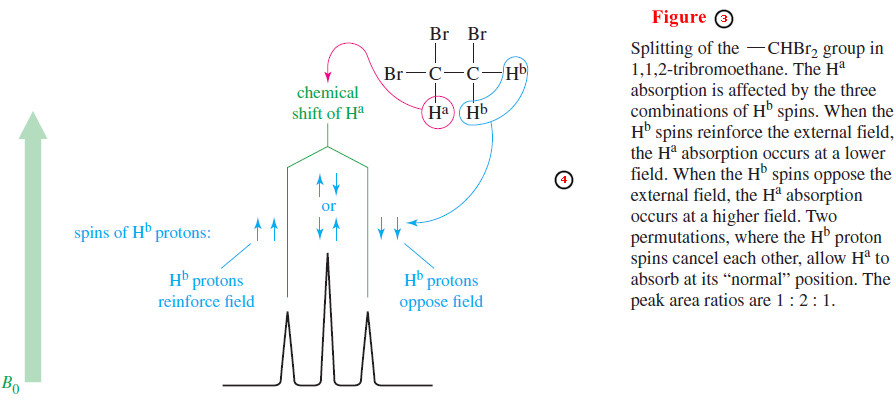

– Proton a in Figure (1) appears as a triplet (at δ 5.7) because there are four permutations of the two Hb proton spins, with two of them giving the same magnetic field (Figure 3).

– When both Hb spins are aligned with the applied field, proton a is deshielded; when both Hb spins are aligned against the field, proton a is shielded; and when the two Hb spins are opposite each other (two possible permutations), they cancel each other out.

– Three signals result, with the middle signal twice as large as the others because it corresponds to two possible spin permutations.

– The two Hb protons do not split each other because they are chemically equivalent and absorb at the same chemical shift.

– Protons that absorb at the same chemical shift cannot split each other because they are in resonance at the same combination of frequency and field strength.

The N+1 Rule

– The preceding analysis for the splitting of 1,1,2-tribromoethane can be extended to more complicated systems.

– In general, the multiplicity (number of peaks) of an NMR signal is given by the N+ 1 rule:

N+1 rule: If a signal is split by N neighboring equivalent protons, it will be split into N+1 peaks.

– The relative areas of the N+1 multiplet that results are approximately given by the appropriate line of Pascal’s triangle:

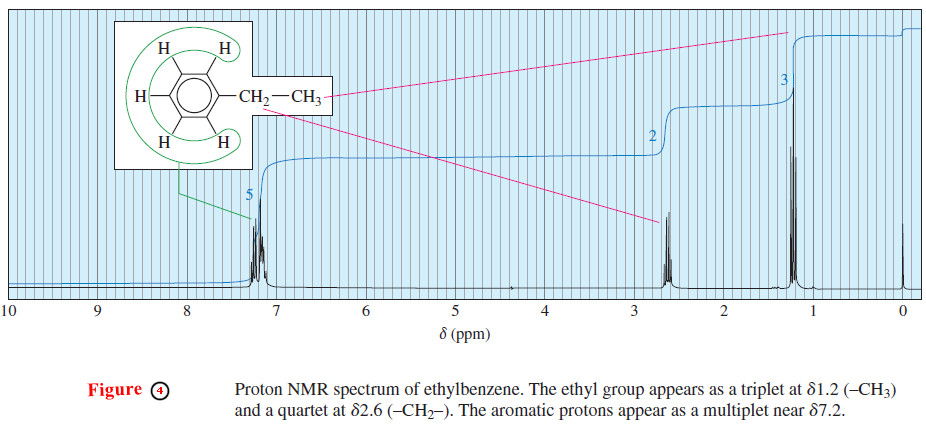

– Consider the splitting of the signals for the ethyl group in ethylbenzene (Figure 4).

– The methyl protons are split by two adjacent protons, and they appear upfield as a triplet of areas 1 : 2 : 1.

– The methylene (CH2) protons are split by three protons, appearing farther downfield as a quartet of areas 1 : 3 : 3 : 1.

– This splitting pattern is typical for an ethyl group. Because ethyl groups are common, you should learn to recognize this familiar pattern.

– All five aromatic protons absorb close to 7.2 ppm because the alkyl substituent has only a small effect on the chemical shifts of the aromatic protons.

– The aromatic protons split each other in a complicated manner in this high resolution spectrum .

– At a lower field with less resolution, these aromatic protons would not be resolved, and they would appear as a slightly broadened single peak.

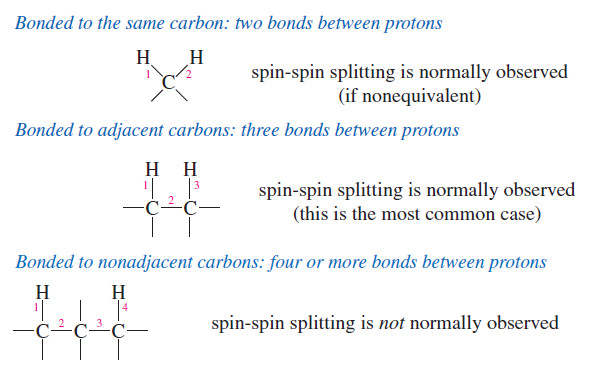

The Range of Magnetic Coupling

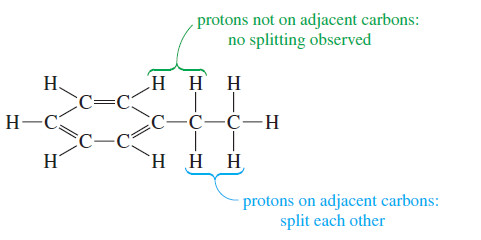

– In ethylbenzene there is no spin-spin splitting between the aromatic protons and the protons of the ethyl group.

– These protons are not on adjacent carbon atoms, so they are too far away to be magnetically coupled.

– The magnetic coupling that causes spin-spin splitting takes place primarily through the bonds of the molecule.

– Most examples of spin-spin splitting involve coupling between protons that are separated by three bonds, so they are bonded to adjacent carbon atoms (vicinal protons).

– Most spin-spin splitting is between protons on adjacent carbon atoms.

– Protons bonded to the same carbon atom (geminal protons) can split each other only if they are nonequivalent.

– In most cases, protons on the same carbon atom are equivalent, and equivalent protons cannot split each other.

– Protons separated by more than three bonds usually do not produce observable spin-spin splitting.

– Occasionally, such “long-range coupling” does occur, but these cases are unusual.

– For now, we consider only nonequivalent protons on adjacent carbon atoms (or closer) to be magnetically coupled.

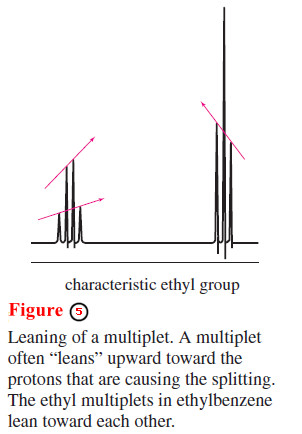

– You may have noticed that the two multiplets in the upfield part of the ethylbenzene spectrum are not quite symmetrical.

– In general, a multiplet “leans” upward toward the signal of the protons responsible for the splitting.

– In the ethyl signal (Figure 5) the quartet at lower field leans toward the triplet at a higher field, and vice versa.

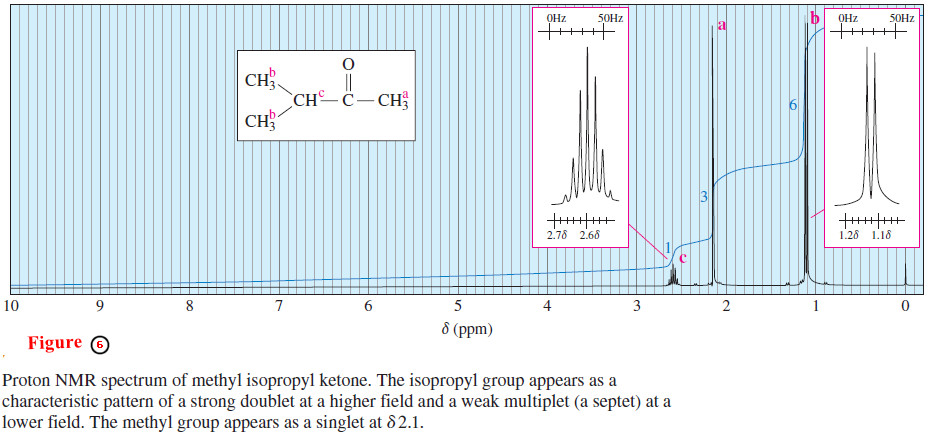

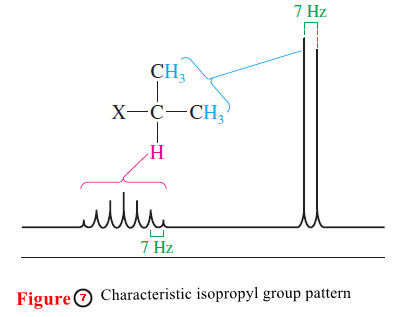

– Another characteristic splitting pattern is shown in the NMR spectrum of methyl isopropyl ketone (3-methylbutan-2-one) in Figure 6.

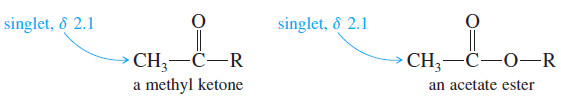

– The three equivalent protons (a) of the methyl group bonded to the carbonyl appear as a singlet of relative area 3, near δ 2.1.

– Methyl ketones and acetate esters characteristically give such singlets around δ 2.1, since there are no protons on the adjacent carbon atom.

– The six methyl protons (b) of the isopropyl group are equivalent.

– They appear as a doublet of relative area 6 at about δ 1.1, slightly deshielded by the carbonyl group two bonds away.

– This doublet leans downfield because these protons are magnetically coupled to the methine proton (c).

– This doublet is also shown in an insert box with the horizontal scale expanded for clarity.

– The vertical scale is adjusted so the peaks fit in the box.

– The methine proton Hc appears as a multiplet of relative area 1, at δ 2.6.

– This absorption is a septet (seven peaks) because it is coupled to the six adjacent methyl protons (b).

– Some small peaks of this septet may not be visible unless the spectrum is amplified, as it is in the expanded insert box.

– The pattern seen in this spectrum, summarized in Figure 7, is typical for an isopropyl group: The methyl protons give a strong doublet at a higher field, and the methine proton gives a weak multiplet (usually difficult to count the peaks) at a lower field.

– Isopropyl groups are easily recognized from this characteristic pattern.

Coupling Constants

– The distances between the peaks of multiplets can provide additional structural information.

– These distances are all about 7 Hz in the methyl isopropyl ketone spectrum (Figures 6 and 7).

– These splittings are equal because any two magnetically coupled protons must have equal effects on each other.

– The distance between adjacent peaks of the Hc multiplet (split by Hb) must equal the distance between the peaks of the Hb doublet (split by Hc ).

– The distance between the peaks of a multiplet (measured in hertz) is called the coupling constant.

– Coupling constants are represented by J, and the coupling constant between Ha and Hb is represented by Jab.

– In complicated spectra with many types of protons, groups of neighboring protons can sometimes be identified by measuring their coupling constants.

– Multiplets that have the same coupling constant may arise from adjacent groups of protons that split each other.

– The magnetic effect that one proton has on another depends on the bonds connecting the protons, but it does not depend on the strength of the external magnetic field.

– For this reason, the coupling constant (measured in hertz) does not vary with the field strength of the spectrometer.

– A spectrometer operating at 300 MHz records the same coupling constants as a 60-MHz instrument.

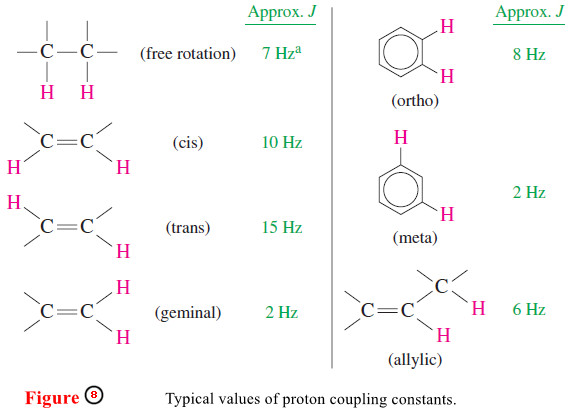

– Figure 8 shows typical values of coupling constants.

– The most commonly observed coupling constant is the 7-Hz splitting of protons on adjacent carbon atoms in freely rotating alkyl groups.

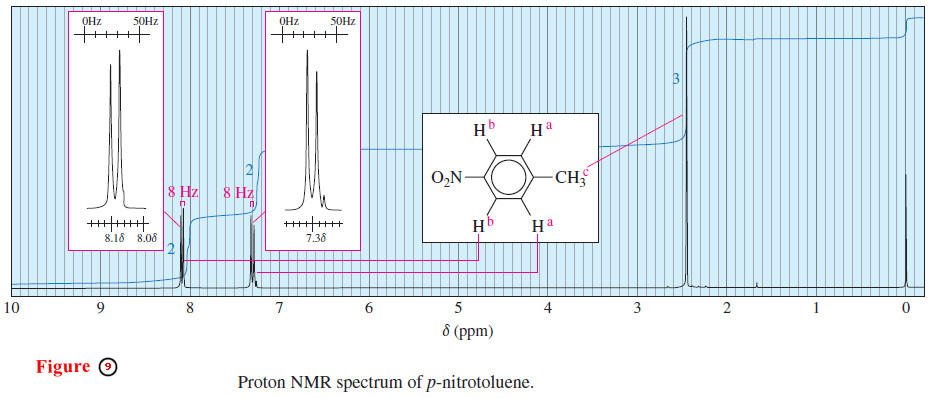

– Splitting patterns and their coupling constants help to distinguish among the possible isomers of a compound, as in the spectrum of p-nitrotoluene (Figure 9).

– The methyl protons (c) absorb as a singlet near δ 2.5, and the aromatic protons appear as a pair of doublets.

– The doublet centered around δ 7.3 corresponds to the two aromatic protons closest to the methyl group (a).

– The doublet centered around δ 8.1 corresponds to the two protons closest to the electron-withdrawing nitro group (b).

– Each proton a is magnetically coupled to one b proton, splitting the Ha absorption into a doublet.

– Similarly, each proton b is magnetically coupled to one proton a, splitting the Hb absorption into a doublet.

– The coupling constant is 8-Hz, just a little wider than the 7-Hz grid in the insert box.

– This 8-Hz coupling suggests that the magnetically coupled protons Ha and Hb are ortho to each other.

– Both the ortho and meta isomers of nitrotoluene have four distinct types of aromatic protons, and the spectra for these isomers are more complex.

– Figure 9 must correspond to the para isomer of nitrotoluene. Coupling constants also help to distinguish stereoisomers.

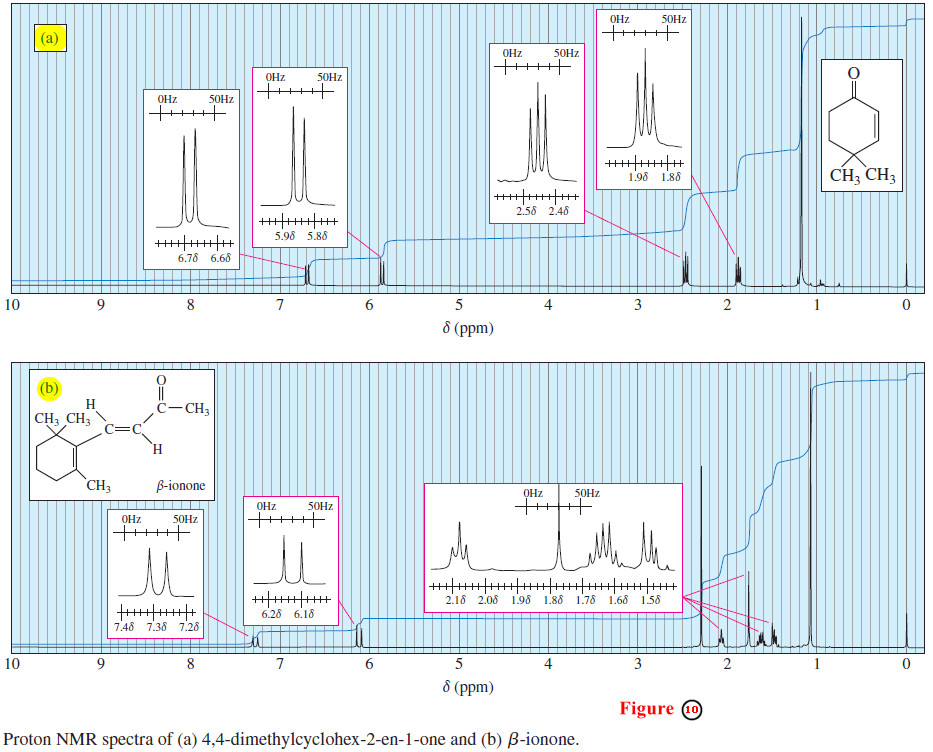

– In Figure 10(a), the 9-Hz coupling constant between the two vinyl protons shows that they are cis to one another.

– In Figure 10(b), the 15-Hz coupling constant shows that the two vinyl protons are trans. Notice that the 9-Hz coupling looks too wide for common alkyl group splitting, represented by the 7-Hz grid in the insert box.

– The 15-Hz coupling looks about double the grid spacing corresponding to the common 7-Hz alkyl group splitting.

References:

- Organic chemistry / L.G. Wade, Jr / 8th ed, 2013 / Pearson Education, Inc. USA.

- Fundamental of Organic Chemistry / John McMurry, Cornell University/ 8th ed, 2016 / Cengage Learningm, Inc. USA.

- Organic Chemistry / T.W. Graham Solomons, Craig B. Fryhle , Scott A. Snyder / 11 ed, 2014/ John Wiley & Sons, Inc. USA.