Aromatic, Antiaromatic, and Nonaromatic Compounds

Aromatic, Antiaromatic, and Nonaromatic Compounds

– Our working definition of aromatic compounds has included cyclic compounds containing conjugated double bonds with unusually large resonance energies.

– At this point we can be more specific about the properties that are required for a compound (or an ion) to be aromatic.

Aromatic compounds

– Aromatic compounds are those that meet the following criteria:

(1) The structure must be cyclic, containing some number of conjugated pi bonds.

(2) Each atom in the ring must have an unhybridized p orbital. (The ring atoms are usually sp2 hybridized or occasionally sp hybridized.)

(3) The unhybridized p orbitals must overlap to form a continuous ring of parallel orbitals. In most cases, the structure must be planar (or nearly planar) for effective overlap to occur.

(4) Delocalization of the pi electrons over the ring must lower the electronic energy.

Antiaromatic compounds

– An antiaromatic compound is one that meets the first three criteria, but delocalization of the pi electrons over the ring increases the electronic energy.

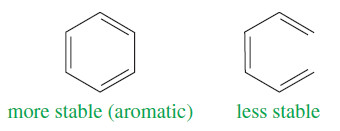

– Aromatic structures are more stable than their open-chain counterparts. For example, benzene is more stable than hexa-1,3,5-triene.

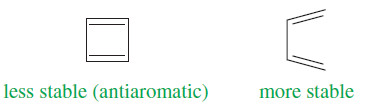

– Cyclobutadiene meets the first three criteria for a continuous ring of overlapping p orbitals, but delocalization of the pi electrons increases the electronic energy.

– Cyclobutadiene is less stable than its open-chain counterpart (buta-1,3-diene), and it is antiaromatic.

Nonaromatic compounds

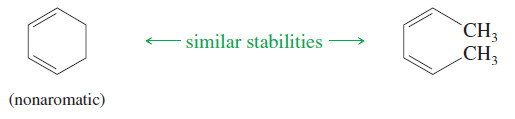

– A cyclic compound that does not have a continuous, overlapping ring of p orbitals cannot be aromatic or antiaromatic. It is said to be nonaromatic, or aliphatic.

– Its electronic energy is similar to that of its open-chain counterpart.

– For example, cyclohexa- 1,3-diene is about as stable as cis,cis-hexa-2,4-diene.

Hückel’s Rule for Aromatic compounds

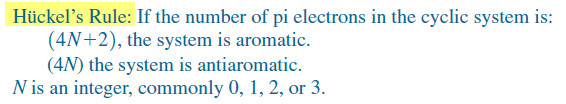

– Erich Hückel developed a shortcut for predicting which of the annulenes and related compounds are aromatic and which are antiaromatic.

– In using Hückel’s rule, we must be certain that the compound under consideration meets the criteria for an aromatic or antiaromatic system.

– To qualify as aromatic or antiaromatic, a cyclic compound must have a continuous ring of overlapping p orbitals, usually in a planar conformation.

– Common aromatic systems have 2, 6, or 10 pi electrons, for N = 0, 1, or 2.

– Antiaromatic systems might have 4, 8, or 12 pi electrons, for N = 1, 2, or 3.

– Benzene is [6]annulene, cyclic, with a continuous ring of overlapping p orbitals.

– There are six pi electrons in benzene (three double bonds in the classical structure), so it is a (4N+2) system, with N = 1.

– Hückel’s rule predicts benzene to be aromatic.

– Like benzene, cyclobutadiene ([4]annulene) has a continuous ring of overlapping p orbitals. But it has four pi electrons (two double bonds in the classical structure), which is a (4N) system with N = 1.

– Hückel’s rule predicts cyclobutadiene to be antiaromatic.

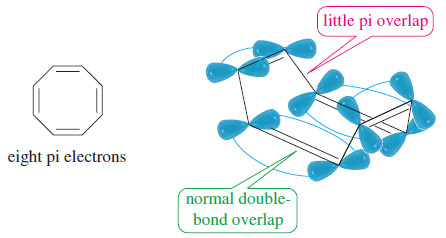

– Cyclooctatetraene is [8]annulene, with eight pi electrons (four double bonds) in the classical structure. It is a (4N) system, with N = 2 .

– If Hückel’s rule were applied to cyclooctatetraene, it would predict antiaromaticity. However, cyclooctatetraene is a stable hydrocarbon with a boiling point of 153°C. It does not show the high reactivity associated with antiaromaticity, yet it is not aromatic either. Its reactions are typical of alkenes.

– Cyclooctatetraene would be antiaromatic if Hückel’s rule applied, so the conjugation of its double bonds is energetically unfavorable.

– Remember that Hückel’s rule applies to a compound only if there is a continuous ring of overlapping p orbitals, usually in a planar system.

– Cyclooctatetraene is more flexible than cyclobutadiene, and it assumes a nonplanar “tub” conformation that avoids most of the overlap between adjacent pi bonds. Hückel’s rule simply does not apply.

Large-Ring Annulenes

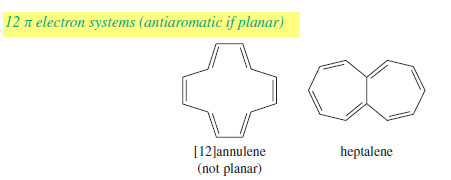

– Like cyclooctatetraene, larger annulenes with (4N) systems do not show antiaromaticity because they have the flexibility to adopt nonplanar conformations.

– Even though [12]annulene, [16]annulene, and [20]annulene are (4N) systems (with N = 3, 4, and 5, respectively), they all react as partially conjugated polyenes.

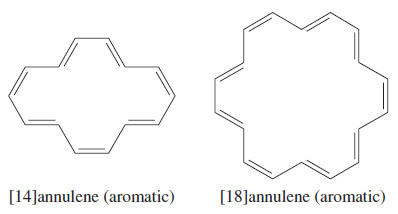

– Aromaticity in the larger (4N+2) annulenes depends on whether the molecule can adopt the necessary planar conformation.

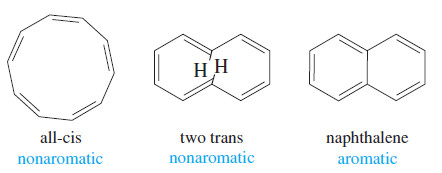

– In the all-cis [10]annulene, the planar conformation requires an excessive amount of angle strain.

– The [10]annulene isomer with two trans double bonds cannot adopt a planar conformation either, because two hydrogen atoms interfere with each other.

– Neither of these [10]annulene isomers is aromatic, even though each has (4N+2) pi electrons, with N = 2.

– If the interfering hydrogen atoms in the partially trans isomer are removed, the molecule can be planar.

– When these hydrogen atoms are replaced with a bond, the aromatic compound naphthalene results.

– Some of the larger annulenes with (4N+2) pi electrons can achieve planar conformations.

– For example, the following [14]annulene and [18]annulene have aromatic properties.

Molecular Orbital Derivation of Hückel’s Rule

– Benzene is aromatic because it has a filled shell of equal-energy orbitals.

– The degenerate orbitals π2 and π3 are filled, and all the electrons are paired. Cyclobutadiene, by contrast, has an open shell of electrons.

– There are two half-filled orbitals easily capable of donating or accepting electrons.

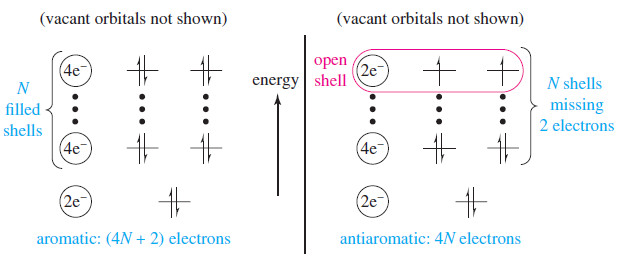

– To derive Hückel’s rule, we must show under what general conditions there is a filled shell of orbitals.

– Recall the pattern of MOs in a cyclic conjugated system.

– There is one all-bonding, lowest-lying MO, followed by degenerate pairs of bonding MOs. (There is no need to worry about the antibonding MOs because they are vacant in the ground state.)

– The lowest-lying MO is always filled (two electrons).

– Each additional shell consists of two degenerate MOs, requiring four electrons to fill a shell.

– The following figure shows this pattern of two electrons for the lowest orbital and then four electrons for each additional shell.

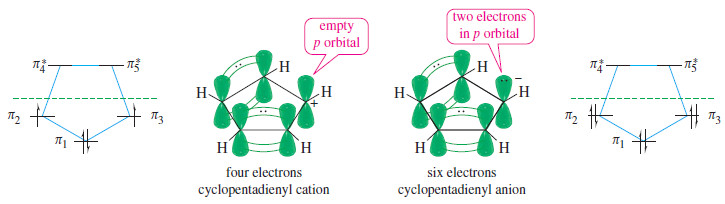

FIGURE: Pattern of molecular orbitals in a cyclic conjugated system. In a cyclic conjugated system, the lowest-lying MO is filled with two electrons. Each of the additional shells consists of two degenerate MOs, with space for four electrons. If a molecule has (4N+2) pi electrons, it will have a filled shell. If it has (4N) electrons, there will be two unpaired electrons in two

degenerate orbitals.

– A compound has a filled shell of orbitals if it has two electrons for the lowest-lying orbital, plus (4N) electrons, where N is the number of filled pairs of degenerate orbitals.

– The total number of pi electrons in this case is (4N+2).

– If the system has a total of only (4N) electrons, it is two electrons short of filling N pairs of degenerate orbitals.

– There are only two electrons in the Nth pair of degenerate orbitals. This is a half-filled shell, and Hund’s rule predicts these electrons will be unpaired (a diradical).

Aromatic Ions

– Up to this point, we have discussed aromaticity using the annulenes as examples.

– Annulenes are uncharged molecules having even numbers of carbon atoms with alternating single and double bonds.

– Hückel’s rule also applies to systems having odd numbers of carbon atoms and bearing positive or negative charges.

– We now consider some common aromatic ions and their antiaromatic counterparts.

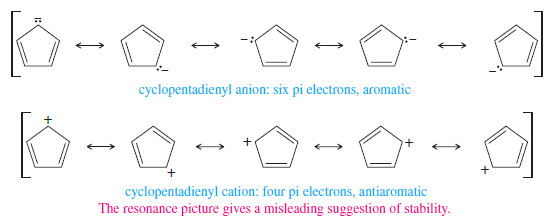

The Cyclopentadienyl Ions

– We can draw a five-membered ring of sp2 hybrid carbon atoms with all the unhybridized p orbitals lined up to form a continuous ring.

– With five pi electrons, this system would be neutral, but it would be a radical because an odd number of electrons cannot all be paired.

– four pi electrons (a cation), Hückel’s rule predicts this system to be antiaromatic.

– With six pi electrons (an anion), Hückel’s rule predicts aromaticity.

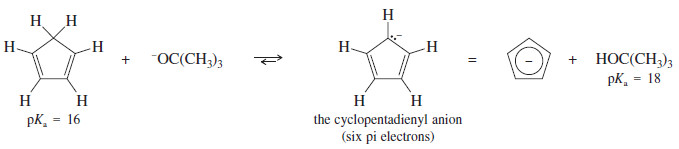

– Because the cyclopentadienyl anion (six pi electrons) is aromatic, it is unusually stable compared with other carbanions.

– It can be formed by abstracting a proton from cyclopentadiene, which is unusually acidic for an alkene.

– Cyclopentadiene has a pKa of 16, compared with a pKa of 46 for cyclohexene. In fact, cyclopentadiene is nearly as acidic as water and more acidic than many alcohols. It is entirely ionized by potassium tert-butoxide:

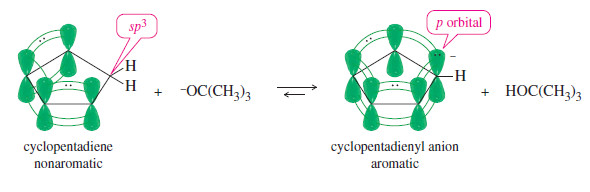

– Cyclopentadiene is unusually acidic because loss of a proton converts the nonaromatic diene to the aromatic cyclopentadienyl anion.

– Cyclopentadiene contains an sp2 hybrid (-CH2-) carbon atom without an unhybridized p orbital, so there can be no continuous ring of p orbitals.

– Deprotonation of the -CH2– group leaves an orbital occupied by a pair of electrons. This orbital can rehybridize to a p orbital, completing a ring of p orbitals containing six pi electrons: the two electrons on the deprotonated carbon, plus the four electrons in the original double bonds.

– When we say the cyclopentadienyl anion is aromatic, this does not necessarily imply that it is as stable as benzene.

– As a carbanion, the cyclopentadienyl anion reacts readily with electrophiles.

– Because this ion is aromatic, however, it is more stable than the corresponding open-chain ion.

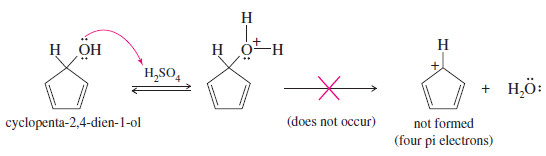

– Hückel’s rule predicts that the cyclopentadienyl cation, with four pi electrons, is antiaromatic.

– In agreement with this prediction, the cyclopentadienyl cation is not easily formed.

– Protonated cyclopenta-2,4-dien-1-ol does not lose water (to give the cyclopentadienyl cation), even in concentrated sulfuric acid. The antiaromatic cation is simply too unstable

– Using a simple resonance approach, we might incorrectly expect both of the cyclopentadienyl ions to be unusually stable.

– Shown next are resonance structures that spread the negative charge of the anion and the positive charge of the cation over all five carbon atoms of the ring.

– With conjugated cyclic systems such as these, the resonance approach is a poor predictor of stability.

– Hückel’s rule, based on molecular orbital theory, is a much better predictor of stability for these aromatic and antiaromatic systems.

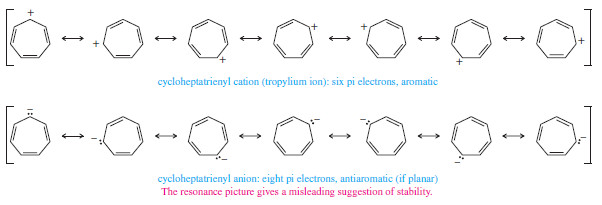

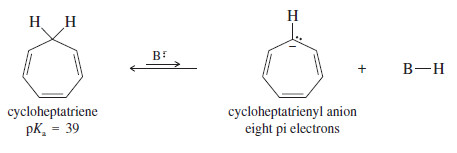

The Cycloheptatrienyl Ions

– As with the five-membered ring, we can imagine a flat seven-membered ring with seven p orbitals aligned.

– The cation has six pi electrons, and the anion has eight pi electrons.

– Once again, we can draw resonance forms that seem to show either the positive charge of the cation or the negative charge of the anion delocalized over all seven atoms of the ring.

– By now, however, we know that the six-electron system is aromatic and the eight-electron system is antiaromatic (if it remains planar).

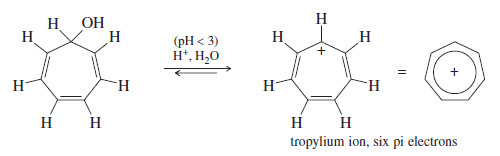

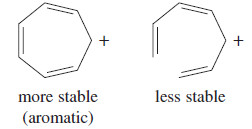

– The cycloheptatrienyl cation is easily formed by treating the corresponding alcohol with dilute (0.01 molar) aqueous sulfuric acid. This is our first example of a hydrocarbon cation that is stable in aqueous solution.

– The cycloheptatrienyl cation is called the tropylium ion. This aromatic ion is much less reactive than most carbocations.

– Some tropylium salts can be isolated and stored for months without decomposing. Nevertheless, the tropylium ion is not necessarily as stable as benzene.

– Its aromaticity simply implies that the cyclic ion is more stable than the corresponding open-chain ion.

– Although the tropylium ion forms easily, the corresponding anion is difficult to form because it is antiaromatic.

– Cycloheptatriene (pKa = 39) is barely more acidic more stable than propene (pKa = 43) and the anion is very reactive.

– This result agrees with the prediction of Hückel’s rule that the cycloheptatrienyl anion is antiaromatic if it is planar.

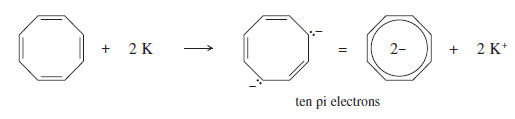

The Cyclooctatetraene Dianion

– We have seen that aromatic stabilization leads to unusually stable hydrocarbon anions such as the cyclopentadienyl anion.

– Dianions of hydrocarbons are rare and are usually much more difficult to form.

– Cyclooctatetraene reacts with potassium metal, however, to form an aromatic dianion.

– The cyclooctatetraene dianion has a planar, regular octagonal structure with C-C bond lengths of 1.40 Å close to the 1.397 Å bond lengths in benzene.

– Cyclooctatetraene itself has eight pi electrons, so the dianion has ten: (4N+2) with N = 2.

– The cyclooctatetraene dianion is easily prepared because it is aromatic.

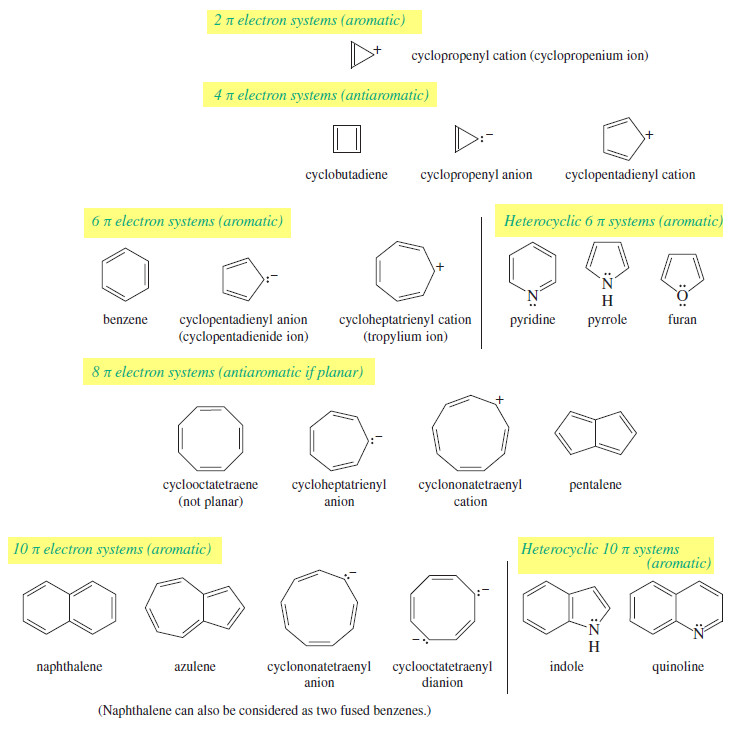

Summary of Annulenes and Their Ions

This list summarizes applications of Hückel’s rule to a variety of cyclic pi systems.

– These systems are classified according to the number of pi electrons: The 2, 6, and 10 π electron systems are aromatic, while the 4 and 8 π electron systems are antiaromatic if they are planar.

References:

- Organic chemistry / L.G. Wade, Jr / 8th ed, 2013 / Pearson Education, Inc. USA.

- Fundamental of Organic Chemistry / John McMurry, Cornell University/ 8th ed, 2016 / Cengage Learningm, Inc. USA.

- Organic Chemistry / T.W. Graham Solomons, Craig B. Fryhle , Scott A. Snyder / 11 ed, 2014/ John Wiley & Sons, Inc. USA.

- Unergraduate Organic Chemistry /Dr. Jagdamba Singh, Dr. L.D.S Yadav / 1st ed, 2010/ Pragati prakashan Educational Publishers, India.